When you imagine giant flying creatures of the past, you might think of pterodactyls, those leathery-winged reptiles swooping through Jurassic skies. But these were mere sparrows compared to the true giants that came later — the azhdarchid pterosaurs, crowned by one of the greatest fliers to ever live: Quetzalcoatlus.

Named after the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl of Aztec legend, Quetzalcoatlus was a marvel of prehistoric engineering. This magnificent pterosaur, with a wingspan that could reach over 10 meters (33 feet) or more, was taller than a giraffe when standing on the ground, yet light enough to launch into flight. Its existence challenges our understanding of what nature can design.

For decades, paleontologists and the public alike have been captivated by this colossal animal. Was it a soaring predator, scanning the land from above for prey? Or a giant stork-like scavenger, stalking the dinosaur herds? The mystery of Quetzalcoatlus still inspires scientists and artists alike, and its legacy as one of the largest known flying animals on Earth is secure.

The Discovery of a Giant

The story of Quetzalcoatlus begins in 1971, deep in the fossil-rich regions of Big Bend National Park, Texas. There, a geology graduate student named Douglas Lawson stumbled upon something extraordinary: huge fossilized bones, far larger than any known pterosaur at the time. The partial wing bones he uncovered suggested a creature that dwarfed any previously discovered flying reptile.

As more bones were studied, a picture emerged of a truly gigantic pterosaur, bigger than any flying creature ever found before. Lawson formally described and named Quetzalcoatlus northropi in 1975. The name honored Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity of Aztec mythology, reflecting the animal’s enormous size and its place in the skies, while “northropi” honored John Northrop, a pioneer in aviation who built flying-wing aircrafts — a fitting tribute for a giant of the air.

This discovery electrified paleontologists. Before Quetzalcoatlus, the largest known pterosaurs had wingspans of around 6 meters, already impressive by today’s standards. But Quetzalcoatlus nearly doubled that, rewriting the record books for flying animals.

Anatomy of a Sky Giant

What made Quetzalcoatlus so incredible?

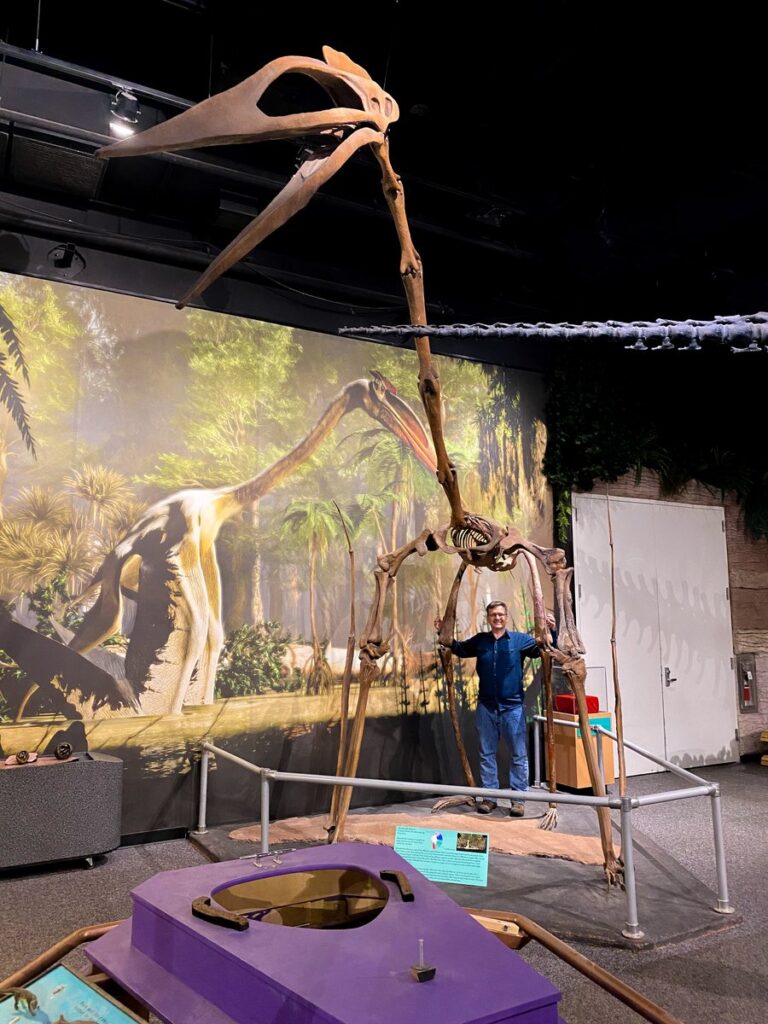

For one thing, its sheer size. Fossil evidence suggests its wingspan could have stretched from 10 to possibly even 12 meters (33–39 feet), making it comparable in wingspan to a small airplane. When standing on the ground, its head would tower about 5 meters (16 feet) high, about the height of a modern giraffe.

Its body was remarkably lightweight — a vital trait for flight. Like other pterosaurs, it had hollow bones similar to modern birds, reducing its mass. Its skull was long and spear-like, perfect for grabbing prey or probing carcasses. The neck was elongated and strong, giving it reach to hunt or scavenge from the ground.

Unlike birds, Quetzalcoatlus had a unique wing structure supported by a single massively elongated fourth finger, which carried a membrane stretching to its legs. Its wings were powerful yet flexible, adapted for soaring over vast distances with minimal effort.

On the ground, Quetzalcoatlus walked on all fours, using its folded wings as front limbs. It was surprisingly graceful for such a huge animal, and paleontologists believe it could move rapidly on land, perhaps stalking prey through the floodplains of Late Cretaceous North America.

How Did It Fly?

One of the most hotly debated questions about Quetzalcoatlus is: how did it get airborne?

Launching a 200–250 kg animal with a 10-meter wingspan isn’t easy. Some early paleontologists suggested it might have struggled to take off, perhaps relying on cliffs or strong winds. But modern research paints a different picture.

Studies of pterosaur anatomy show that their massive forelimbs acted like powerful catapults. Using a “quadrupedal launch” — pushing off with both hindlimbs and then vaulting explosively with their folded wings — they could spring into the air with surprising speed, much like a vampire bat launching from the ground. This style of launch would have given Quetzalcoatlus enough lift to become airborne even on flat ground, allowing it to glide powerfully over its territory.

Once in the air, Quetzalcoatlus was a master of soaring. Its long wings and high aspect ratio were ideal for exploiting thermals — columns of warm rising air — enabling it to travel enormous distances while expending little energy, much like modern albatrosses.

Life in the Late Cretaceous

Quetzalcoatlus lived around 70–66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period. North America at that time was very different from today. Vast river systems, subtropical floodplains, and warm coastal plains stretched across the region. Herds of hadrosaurs and ceratopsians roamed the landscape, while giant tyrannosaurs stalked as apex predators.

Into this ecosystem strode Quetzalcoatlus, one of the strangest giants of the time. Its lifestyle is still debated:

- Some scientists think it was a scavenger, patrolling the plains and using its long neck and pointed beak to pick flesh from dinosaur carcasses.

- Others suggest it actively hunted, perhaps snapping up small dinosaurs, baby ceratopsians, or lizards, using its beak like a deadly spear.

What is clear is that its size and speed would have made it a dominant force wherever it went. Smaller predators would have given it a wide berth, unwilling to challenge such a towering giant.

A Symbol of Prehistoric Majesty

There is something deeply compelling about Quetzalcoatlus. It pushes the boundaries of what we believe flying animals can do. With its huge wingspan, giraffe-like stance, and efficient soaring style, it represents one of nature’s most extraordinary evolutionary experiments.

Modern engineers study Quetzalcoatlus to inspire lightweight flying robots and efficient aircraft designs. Its combination of powerful launch ability, vast wings, and ultra-light skeleton is an engineering marvel — one that emerged from nature 70 million years ago.