Introduction

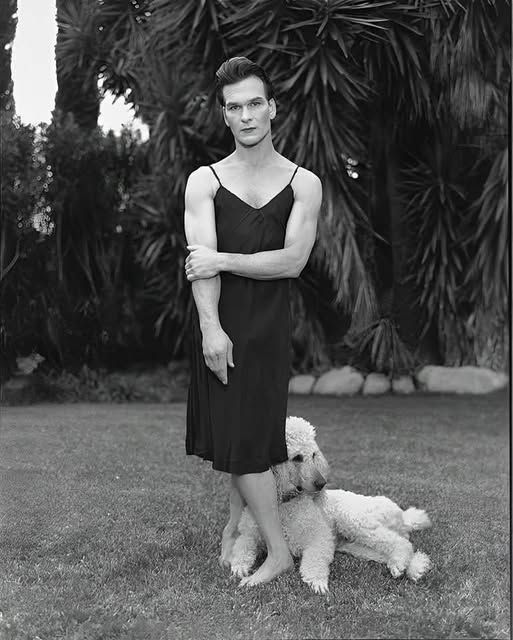

In the digital age—an era flooded with manipulated images and AI-generated art—it is increasingly difficult to discern the real from the artificial. So when a black-and-white photograph surfaces, showing a man confidently wearing a dress in what appears to be a professionally staged portrait, it commands attention. Viewers pause, not just because the subject challenges traditional gender norms, but also because of the lingering question: is it real?

“Yes, the image is real and appears to be an authentic black-and-white photograph—likely a professionally staged portrait,” begins the analysis. “The man in the image is wearing a dress and standing confidently, suggesting it may have been taken for artistic, fashion, or statement-making purposes.” This observation is more than a technical validation of the photo’s authenticity; it’s a window into the evolving dialogue surrounding gender, identity, and art. This essay aims to explore the broader implications of such an image, including its cultural resonance, historical context, and the way it reclaims visibility for those long sidelined by mainstream norms.

I. The History of Men in Dresses: A Cultural Perspective

To understand the impact of such a photo, one must first dispel the myth that men in dresses are a modern anomaly. In fact, the association of dresses solely with femininity is a relatively recent Western construct. Ancient societies were far less rigid in their gendered clothing distinctions.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, for instance, men commonly wore tunics—loose garments similar in structure to what we might now call dresses. Scottish Highlanders wore kilts, Japanese men wore yukatas, and in many African, South Asian, and Middle Eastern cultures, robes and draped garments have long been common male attire. These garments were not considered emasculating but functional, cultural, and often ceremonial.

It wasn’t until the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution in the West that fashion began to harden gender binaries, emphasizing trousers and tailored jackets for men and corsets and skirts for women. With this change came deeper ideological shifts: masculinity became equated with rationality and control, while femininity was associated with emotionality and ornamentation.

The image in question—a black-and-white photograph of a man in a dress—stands in deliberate defiance of these imposed norms. Rather than an act of absurdity, it is a reclamation of a historically complex and culturally rich tradition.

II. The Staged Portrait: Intention, Performance, and Power

The image’s staging is intentional and arresting. Portraiture, especially in black and white, has long been a medium that conveys depth, introspection, and timelessness. When paired with subversive fashion, it becomes more than an aesthetic decision—it becomes a statement.

The man’s confident posture—unapologetic, composed, and strong—undermines any notion that wearing a dress is a submissive or weakened form of expression. Rather than laughing at or ridiculing societal expectations, the image seems to transcend them altogether. This is not drag, nor is it parody. It is presentation, authenticity, and quiet rebellion.

Portrait photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe, Diane Arbus, and Zanele Muholi have long used their craft to explore the boundaries of gender, sexuality, and identity. Their subjects, often marginalized or misunderstood by society, are presented not as anomalies but as icons of resilience and beauty.

This image sits within that tradition. It is art not simply because of the frame, lighting, or composition, but because of its capacity to evoke. It challenges the viewer to reflect: Why does this feel transgressive? Why is a man in a dress so powerful?

III. Gender Expression as a Form of Art and Identity

In contemporary discourse, gender is increasingly understood not as binary but as a spectrum. The photograph, by showcasing a male-presenting individual in a traditionally feminine garment, disrupts the viewer’s conditioned responses. It makes us question the assumptions we place on clothing, posture, and presentation.

Gender expression, especially in fashion, is both deeply personal and highly political. What we wear often reflects who we are, how we wish to be seen, and how we defy or comply with societal expectations. For men who embrace traditionally feminine aesthetics, the stakes are often high. The world responds with judgment, curiosity, or aggression. To pose for such a portrait, then, is not just an artistic act—it is an act of courage.

Moreover, the calm and confidence exuded by the subject dismantles the notion that femininity is weak. Here, the dress becomes a symbol of strength—not because it mimics masculinity, but because it embraces vulnerability as power. This nuanced understanding of identity is central to much of today’s gender-fluid and nonbinary art and activism.

IV. The Photograph in the Age of AI and Digital Manipulation

One of the most frequently asked questions about such images today is: “Is it real?” The rise of artificial intelligence and digital photo manipulation has made skepticism a default mode. AI-generated portraits can replicate photographic realism to uncanny degrees. Deepfakes blur the line between fiction and documentation.

In this context, the image’s authenticity becomes part of its power. “If you’re asking whether the person is digitally altered or AI-generated—the answer is no, it does not appear AI-generated or fake.” This confirmation reassures the viewer: there is a real person here. A human being made the choice to wear this dress. A photographer, likely human as well, made the choice to capture it.

Authenticity matters not just for documentation, but for meaning. When a real human being steps into a traditionally gendered role and subverts it, it carries a weight that synthetic images cannot replicate. AI can simulate aesthetics, but it cannot simulate experience, pain, joy, or lived rebellion.

In this way, the photograph is a bulwark against the growing impersonality of digital culture. It reminds us that real people, not algorithms, are the true engines of artistic and social change.

V. Masculinity, Vulnerability, and Reclamation

Traditional masculinity is often built on foundations of dominance, control, and emotional suppression. Images like this one—of a man confidently embracing symbols associated with femininity—are often viewed as threatening because they challenge the rigidity of those foundations.

But what if the true strength lies in vulnerability? What if masculinity could expand, evolve, and incorporate softness, creativity, and emotional expression?

This photograph reclaims masculinity not by denying it, but by expanding its boundaries. It suggests that men, too, can wear beauty. They can enjoy fabric that flows rather than restricts. They can stand tall in lace, silk, or tulle—not as clowns or deviants, but as humans.

This form of reclamation is not new. Artists like David Bowie, Prince, and Billy Porter have long blurred the lines of gender in their fashion choices. Each did so not just for shock value but to claim space for a broader, more inclusive understanding of manhood. This photograph continues that legacy—intimate, graceful, and defiant.

VI. Reception and Cultural Tension

Of course, not all responses to such imagery are supportive. The internet is quick to polarize, and gender-nonconforming expressions still face widespread resistance. Some see it as provocative, unnatural, or even political propaganda.

And yet, these very reactions reveal the deeper discomfort society holds around fluidity. When rigid categories are challenged, those who benefit from them feel unsettled. This image becomes a mirror, reflecting not just the subject but the viewer’s prejudices and beliefs.

Art, when successful, provokes. It invites conversation and even discomfort. In that sense, the photograph does exactly what great art is meant to do—it stirs something deep, unresolved, and essential.