In the ideological battleground of the Cold War, history often became a weapon as much as a guide. Among émigré and conservative Polish intellectuals in the 1960s, a powerful narrative emerged that recast the historic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, particularly under the Jagiellonian dynasty, as the “shield of Western civilization.” This vision did not merely recall the grandeur of a vanished realm but reasserted Poland’s historical role as a defender of Christianity, liberty, and Western political ideals against both Eastern despotism and modern totalitarianism. The Polish Jagiellonian Realm, in this narrative, became more than a historical curiosity—it became a symbol of resistance, identity, and ideological defiance amid Soviet domination.

The Jagiellonian Legacy: A Multiethnic, Western-Oriented Realm

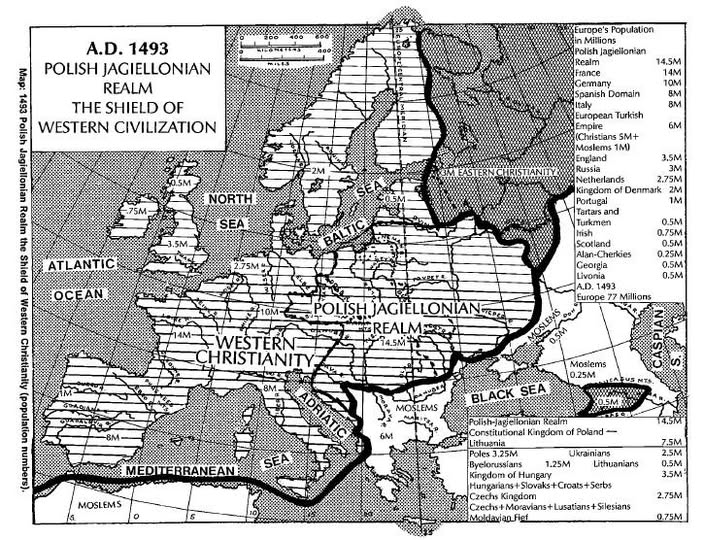

The Jagiellonian dynasty, which ruled from 1386 to 1572, presided over one of the largest and most culturally diverse political entities in Europe. What began as a dynastic union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania blossomed into a vast realm stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea, encompassing territories of present-day Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, and parts of Russia and Latvia. By the Union of Lublin in 1569, the two states formally merged into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth—an elective monarchy governed by a unique system of noble democracy.

From the perspective of 20th-century Polish exiles, the Commonwealth was not just a state—it was a civilizational project. It represented a distinctive blend of Western political philosophy and Eastern geopolitical reality. It balanced monarchic authority with a robust parliamentary system, upheld the rule of law through a codified legal tradition, and fostered religious pluralism unusual for its time. In this light, the Jagiellonian state was a precursor to modern liberal democracies and a bastion of Western values on the edge of an often hostile East.

Poland as the Rampart of Christianity and Europe

The metaphor of Poland as the “bulwark of Christianity” (Antemurale Christianitatis) has deep historical roots. Throughout the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth fought numerous wars to repel the incursions of non-Christian powers: the Teutonic Knights, the Crimean Tatars, the Tsardom of Russia, and the expanding Ottoman Empire. Victories at battles like Orsha (1514) and Khotyn (1621) were heralded not only as military triumphs but as defenses of Christendom itself.

This role was dramatically affirmed in 1683 during the Battle of Vienna, when King John III Sobieski of Poland led a Christian coalition that halted the Ottoman advance into Central Europe. For émigré intellectuals in the 1960s, this episode became emblematic. It signified a moment when Poland acted as the sword and shield of Western Europe—a peripheral yet essential defender of European civilization. The Jagiellonian tradition, with its deep Catholic roots and strong chivalric culture, was idealized as the frontline in the clash of civilizations.

The Commonwealth’s Republican Ideals and Noble Democracy

While the political system of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was certainly flawed and often chaotic, it was nevertheless profoundly ahead of its time in several respects. The Golden Liberty (Złota Wolność), a political doctrine of the Polish nobility, emphasized checks on monarchical power, legal equality among nobles, and legislative authority through the Sejm, or parliament. Though exclusionary by modern standards—only the szlachta (nobility) enjoyed these rights—it represented a kind of proto-republicanism that contrasted sharply with the absolute monarchies dominating Europe.

In the 1960s, Polish exiles in the West seized on this legacy to frame their nation’s past as one committed to liberty and self-governance. Against the backdrop of Soviet authoritarianism, the Commonwealth appeared as a model of participatory government and legal restraint. Historians and publicists like Józef Mackiewicz, Jerzy Giedroyc, and Czesław Miłosz invoked this history not out of nostalgia alone, but as a deliberate contrast to the collectivist and autocratic ideology of the USSR. For them, the Commonwealth was not just an extinct polity—it was a philosophical and cultural counterweight to the East.

The 1960s: Reclaiming History as Ideological Resistance

In the postwar world order, Poland found itself under the shadow of Soviet domination. The 1960s, marked by heightened Cold War tensions, witnessed a renewed interest among Polish émigré communities—especially in Paris, London, and North America—in reasserting Poland’s historical agency. The mythos of the Jagiellonian Commonwealth provided a rich vein of material for constructing a counter-narrative to Soviet hegemony.

Journals like Kultura (Paris-based and edited by Jerzy Giedroyc) became platforms for this intellectual revival. Writers associated with this movement sought to transcend narrow nationalism and reimagine Poland as the center of a multicultural and pluralistic civilization. In this vision, the Polish state was not an ethnic monolith but a shared home of Poles, Lithuanians, Ruthenians (Ukrainians and Belarusians), Jews, and others—a place where Eastern and Western traditions met in dialogue rather than conquest.

By highlighting the Commonwealth’s legacy of religious tolerance—such as the Warsaw Confederation of 1573, which guaranteed freedom of conscience—they presented a model of coexistence deeply at odds with both Nazi genocidal nationalism and Stalinist repression. The Jagiellonian realm became a historical ideal of coexistence, one in which liberty and law held sway over tyranny and ideology.

Soviet Communism as the New Eastern Threat

For Polish intellectuals steeped in the trauma of World War II and the betrayal of Yalta, the Soviet Union was not merely a geopolitical power—it was an ideological colonizer. The narrative of the Jagiellonian Commonwealth as the shield of the West was reborn as a form of psychological and cultural resistance. In the Cold War imagination, just as the Commonwealth had once blocked the Ottoman Crescent or Muscovite Orthodoxy, so too had modern Poland suffered for standing against Bolshevik atheism and collectivist autocracy.

The Warsaw Uprising (1944), brutally suppressed while the Red Army waited across the Vistula, was recast in the émigré imagination as a modern version of this sacrificial defense of Western values. The Soviet imposition of communism on Poland after the war was interpreted as a historical recurrence: once more, the East was encroaching, and once more, Poland was paying the price for its location between civilizations.

Thus, the memory of the Jagiellonian state served not merely as a lament for lost grandeur but as a defiant reassertion of Polish identity and its alignment with the West. By invoking a time when Poland had stood strong and free, émigré intellectuals could articulate a vision of Poland not as a satellite, but as a spiritual and cultural leader.

Romanticism, Realpolitik, and National Myth

Of course, the image of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as the “shield of the West” is as much a romanticized myth as it is a historical interpretation. The Commonwealth had many internal contradictions—noble liberties coexisted with serfdom, and political paralysis (the liberum veto) led to eventual collapse. The multiethnic harmony it celebrated could be disrupted by rebellion and coercion, particularly in Ukrainian and Jewish communities. Its military campaigns were often defensive, but not always; its internal politics, frequently more factional than united.

Yet in times of national crisis, myths often serve functions that facts cannot. The 1960s émigré revival of the Jagiellonian ideal was not about denying historical complexity but about using selective memory to shape national resilience. It was an attempt to root contemporary anti-communism in a proud and expansive tradition. In doing so, it challenged both Soviet historiography and Western indifference to Eastern Europe’s historical depth.

Indeed, by portraying Poland as a civilizational mediator, these intellectuals also pushed back against Western Cold War narratives that saw Eastern Europe merely as a buffer zone. They insisted instead on Poland’s full membership in the Western tradition—a nation that had fought and died for the values that Europe itself professed to hold dear.

The Jagiellonian Idea and Federalism

Another notable element of the émigré discourse was the revival of the federalist idea associated with the Jagiellonian tradition. Polish thinkers like Józef Piłsudski in the early 20th century had already drawn upon this legacy when proposing a post-imperial federation of Central and Eastern European peoples (the “Międzymorze” or Intermarium). In the 1960s, similar ideas resurfaced as intellectuals speculated about a post-Soviet order in which the nations of Eastern Europe could cooperate in a renewed spirit of autonomy and mutual respect.

The Jagiellonian Commonwealth, with its intricate balance between Poland and Lithuania and its decentralized structure, was cited as a model for such future arrangements. Though historically imperfect, it offered an alternative to both imperial domination and narrow nationalism. It suggested that unity need not require uniformity, and that political cooperation across ethnic and linguistic lines was possible.

Conclusion: Memory as Identity, History as Resistance

In the turbulent ideological landscape of the 1960s, when Poland groaned under the weight of Soviet control, the revival of the Jagiellonian legacy served as both consolation and defiance. For Polish intellectuals in exile, it was a way to reclaim national dignity, assert Western identity, and imagine a future beyond occupation and oppression. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, under the Jagiellonian dynasty, was not simply a medieval state but a symbol—a testament to Poland’s historic mission as the “shield of Western civilization.”

By invoking this myth, these thinkers resisted the flattening narratives of Cold War geopolitics. They reminded the world that Poland was not an artificial construct of postwar diplomacy, nor a passive pawn in superpower games, but a nation with deep historical roots, a tradition of pluralism, and a legacy of defending the values that now defined the free world.

Today, as Europe continues to grapple with questions of identity, borders, and the tension between liberalism and authoritarianism, the Jagiellonian idea still resonates. It reminds us that geography need not dictate ideology, that small nations can play outsized roles in the defense of shared values, and that the past, when thoughtfully remembered, can be a wellspring of courage in uncertain times.