In the frozen annals of Antarctic exploration, the names most often remembered are those who died dramatic deaths or staked bold claims. Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton loom large in the public memory, their expeditions documented in headlines, their failures mythologized as tragic heroism. Yet there is another name that deserves to be etched into the icy canon of polar legacy: Douglas Mawson — a scientist, survivor, and quiet hero.

Mawson was not the kind of man who craved glory. His soul leaned more toward geology than grandeur. Born in England and raised in Australia, Mawson was a scholar and a naturalist. He believed in Antarctica not as a stage for imperial competition but as a vast, frozen laboratory teeming with secrets waiting to be uncovered. His 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition was not primarily a race to the Pole but a pioneering effort to map, study, and understand one of the last untouched frontiers on Earth.

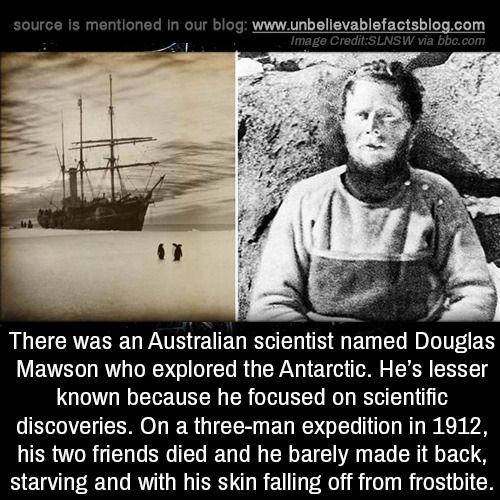

But Mawson’s greatest claim to fame would not come from scientific discovery alone. In 1912, a routine sledging journey with two companions turned into one of the most horrific survival stories in exploration history. With both teammates dead, food nearly gone, and his body ravaged by frostbite and starvation, Mawson somehow made it back alone across the most inhospitable terrain on the planet.

His tale is less romanticized than others, perhaps because it lacks the clean ending of martyrdom or the daring bravado of rescue missions. But it is no less extraordinary. Douglas Mawson stands not just as a scientist or an explorer, but as a symbol of human resilience in the face of absolute desolation.

This is his story — a story of endurance, science, and the stark, white silence of the Antarctic.

Douglas Mawson was born on May 5, 1882, in Shipley, Yorkshire, England. At the age of two, his family immigrated to Australia, settling in Sydney. From an early age, Mawson displayed a keen interest in the natural world. He studied mining engineering and geology at the University of Sydney and graduated in 1902. His fascination with Earth’s ancient secrets led him to lecture in geology at the University of Adelaide by his mid-twenties.

Mawson’s first brush with polar exploration came when he joined Sir Ernest Shackleton’s 1907–1909 Nimrod Expedition. As part of the scientific team, Mawson became one of the first men to reach the South Magnetic Pole alongside Edgeworth David and Alistair Mackay. This journey — treacherous, grueling, and often improvisational — solidified his reputation as a serious scientist and a tough field man. But unlike many others, Mawson returned from that expedition with something more than adventure stories — he brought back valuable scientific data and a deepening desire to explore further.

His mind turned toward East Antarctica — a vast and largely unknown sector of the continent. This region was closer to Australia and thus of particular interest to Australian geologists and climatologists. While Shackleton and Scott aimed their ambitions toward the South Pole, Mawson had a different goal: to lead a full-scale scientific expedition that would establish research stations, map uncharted coastlines, and collect data on everything from geology and magnetism to biology and weather systems.

In 1911, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) was born. Unlike previous expeditions, which had relied heavily on imperial funding and prestige, Mawson’s team was supported by Australian and New Zealand institutions, with additional funds raised through public lectures and private donations. The venture was logistically ambitious and deeply rooted in science.

As the AAE departed Hobart in December 1911 aboard the ship Aurora, few suspected that Mawson’s real trial — the one that would define his legacy — lay not in data collection, but in survival.

The main base of operations for the AAE was established at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay — a site later described by Mawson as “the windiest place on Earth.” Blasted by katabatic winds that could exceed 200 km/h (125 mph), the base quickly became a proving ground for the team’s resilience. Nevertheless, over 18 months, Mawson and his men set about conducting some of the most comprehensive scientific studies of the Antarctic to date.

They built meteorological stations, collected geological specimens, documented wildlife, and explored over 2,600 kilometers of unknown coastline and inland territory. The scope of their work was remarkable, and despite severe weather, they maintained discipline and scientific rigor. Their efforts would later influence global understanding of polar climates and geological history.

But among the many sledging journeys planned from Cape Denison, one in particular would change everything. In November 1912, Mawson led a three-man party to explore the far eastern coastal region. His companions were Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz and British Army lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis. Their plan was simple: push eastward, gather samples, and return in just over a month.

The terrain was brutal — crevasses hidden by snow bridges, temperatures plummeting well below -40°C, and constant exposure to the biting wind. Yet they made good progress, covering hundreds of kilometers. Then, on December 14, tragedy struck.

Ninnis, walking beside one of the sledges that carried most of their supplies, fell through a hidden crevasse. The snow bridge gave way without warning, and he, along with the sledge, six of their strongest dogs, and most of the food, vanished into the abyss. Mawson and Mertz peered into the crevasse but saw only darkness. Ninnis was gone.

The two remaining men were left with barely enough supplies to survive a week.

With most of their food gone and hundreds of kilometers between them and Cape Denison, Mawson and Mertz faced a terrible choice: attempt a risky return with what little they had, or perish in place. They chose to fight for life.

For nourishment, they killed their remaining dogs, eating what meat they could salvage and feeding on the livers for sustenance. At the time, they didn’t know that husky liver contains dangerously high levels of vitamin A — a toxic dose for humans. Both men soon began showing symptoms of hypervitaminosis A: severe abdominal pain, peeling skin, hair loss, and nausea.

Mertz deteriorated rapidly, slipping into hallucinations and unconsciousness. Mawson recorded his final days with clinical precision in his journal, noting changes in behavior and vital signs, even as he himself weakened. On January 8, 1913, Mertz died in the tent.

Mawson was now alone — starving, frostbitten, and still over 100 miles from base camp. The soles of his feet were detaching due to frostbite, forcing him to wrap them in cloth and bandage. At times he fell into crevasses and had to claw his way out using a makeshift rope harness. His body was so emaciated that his bones ached from lack of insulation. Still, he pressed on.

Each day, he crawled or limped a few miles. Each night, he erected a frail tent, melting snow for water and rationing scraps of food. He hallucinated, dreamt of voices and music, saw phantom sledges and companions. At one point, he even prepared to end his life — but instead tore up the note he had written and chose to go on.

Against every conceivable odd, on February 8, 1913 — more than a month after setting out alone — Mawson staggered into Cape Denison. He was gaunt, ghost-like, barely alive.

When Mawson returned, his timing was both miraculous and tragic. Just hours earlier, the Aurora, the expedition’s supply and return ship, had departed, not expecting any survivors from his party. A small rescue team had been left behind just in case, and they greeted the returning Mawson with stunned disbelief.

Despite being too weak to speak more than a few words, Mawson refused immediate evacuation. The ship had to be signaled and brought back — a process that took weeks — and Mawson chose to remain to continue the scientific documentation of the expedition’s findings.

This decision reflects the depth of his commitment to science. Even after his ordeal, he prioritized the completion and preservation of the research over his own well-being. Eventually, Mawson returned to Australia in March 1914, a shell of the man who had left, but alive, and carrying data that would reshape polar science

Mawson returned to Australia a hero, but one more respected than celebrated. Unlike the romanticized figures of Scott or Shackleton, his fame came not from conquest or disaster, but from science and sheer survival. He resumed his academic career at the University of Adelaide and spent the rest of his life contributing to geology and polar studies.

In 1929, he led another Antarctic mission — the British, Australian, and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE). This expedition, conducted over two summers, combined scientific exploration with political claims, helping to establish Australia’s territorial presence in Antarctica.

He was knighted in 1914, awarded numerous scientific honors, and continued to publish scholarly work well into his later years. His book The Home of the Blizzard remains a seminal work in exploration literature, detailing both the scientific findings and the horrors of his journey.

Yet Mawson never became a household name outside academic circles. Perhaps this is because he lacked the flair for public drama. Or perhaps it is because his story, rooted in cold endurance and quiet brilliance, doesn’t lend itself to romantic simplification.

But his impact is undeniable. He mapped vast regions of the Antarctic, collected invaluable geological specimens, and established a legacy of scientific exploration that continues to influence polar research today. The Australian Antarctic Division’s headquarters in Tasmania is named in his honor, as is Mawson Station — one of Australia’s key research bases in Antarctica.

Douglas Mawson never set out to be a legend. He was a man of science who found himself at the edge of human endurance. His journey through the white silence of Antarctica is one of the most astonishing survival stories in recorded history — a tale of intellect, grit, and profound resilience.

Where others sought glory, Mawson sought knowledge. Where others fell, he rose — frostbitten, starving, but unbroken. His legacy is not carved in the marble of monuments, but in the quiet reverence of scientists, explorers, and those who know that true greatness doesn’t always roar. Sometimes, it walks alone across a frozen wasteland, refusing to die, simply because it must go on.

Douglas Mawson showed the world that even in the most lifeless landscape on Earth, the human spirit — driven not by conquest, but by curiosity — can survive.

And in that survival lies something greater than fame. It lies in truth.