Caroline “Carrie” Celestia Ingalls Swanzey, born August 3, 1870, lived in the shadows of American literary fame, her legacy often eclipsed by the success of her older sister, Laura Ingalls Wilder. Yet her life, though less celebrated, is no less remarkable. Carrie’s journey—marked by movement, illness, devotion to family, and professional resilience—embodies the spirit of the American frontier and the quiet strength of women who carved a life from hardship and perseverance.

Early Life on the Move

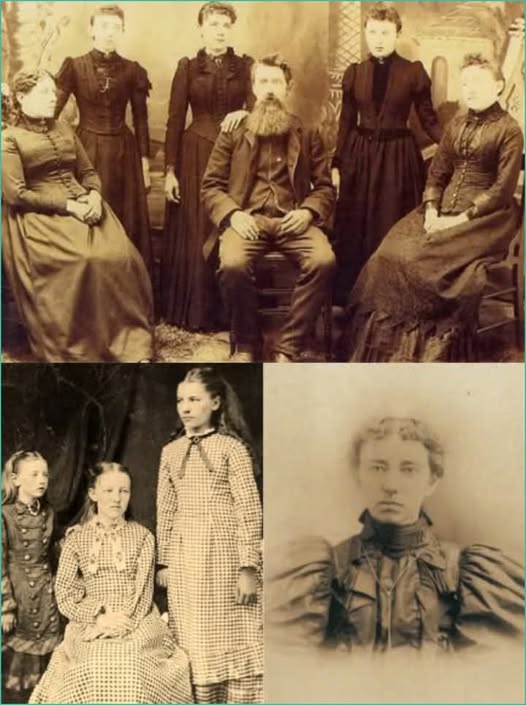

Born in Montgomery County, Kansas, Carrie was the third child of Charles (“Pa”) and Caroline (“Ma”) Ingalls, a family whose life would later become immortalized in the Little House series. Her birth came at a time when the Ingalls family was constantly uprooting, chasing the elusive promise of fertile land and a better life. This nomadic childhood shaped Carrie’s adaptable spirit and her ability to find roots in even the most challenging circumstances.

Her earliest years were spent moving across the Midwest: from Kansas to Wisconsin, then Minnesota, Iowa, and finally, South Dakota. This itinerant lifestyle was typical of many American pioneer families but especially strenuous for a child of delicate health like Carrie. Despite her frailty, Carrie kept pace with her family’s rigorous journey, developing the quiet fortitude that would come to define her adult years.

Carrie makes her first appearance in Laura’s book Little House in the Big Woods, albeit as a baby, and her presence grows in the series as a character marked by sweetness and sensitivity. As the series progresses—particularly after their sister Mary loses her eyesight—Carrie takes on greater responsibilities and visibility, even if her own voice remains understated.

A Quiet Childhood Among Strong Voices

Carrie’s childhood was set against the backdrop of great change and hardship. The family faced crop failures, harsh winters, and the slow disappearance of the open frontier. Each trial demanded not only hard physical labor but emotional endurance. For Carrie, who often suffered from ill health and a slight build, the demands were even greater.

The Dakota Territory, where the family finally settled, was an unforgiving land. Winters were brutal, and the isolation profound. Yet this is where Carrie truly came of age. In De Smet, South Dakota, she attended school, supported her family, and began to show an early interest in writing and publishing. Though she never gained Laura’s storytelling fame, Carrie’s passion for the printed word led her down a parallel path.

She briefly entertained the idea of becoming a teacher, a common occupation for women of her time. But teaching did not hold her interest or match her temperament. It was in the world of newspapers—specifically the technical and editorial side—that Carrie found her calling.

The Newspaper Woman

Carrie’s foray into the newspaper industry began at the De Smet News, and later, more significantly, at the Leader. Working initially in typesetting, layout, and distribution, she quickly developed a strong command of the trade. In a male-dominated profession, she stood out for her dedication and skill, mastering tasks that ranged from editing to bookbinding.

It was during this period that she caught the attention of E.L. Senn, a newspaper magnate who operated dozens of small newspapers throughout South Dakota. Impressed by her capabilities, he offered her more challenging roles—managing newspapers across various towns in the region. Carrie traveled extensively across South Dakota under Senn’s employment, often working in remote and rugged towns where she served not just as a printer but often as the de facto editor and manager.

In an era when women rarely held such positions of responsibility, Carrie’s achievements were groundbreaking. Her contributions, though not often publicly acknowledged at the time, were integral to the success of the publications she served. It was her quiet competency, her refusal to be defined by her gender or her health, that made her exceptional.

A Time of Trial: Health and Homesteading

Like many members of her family, Carrie struggled with chronic health issues throughout her life. Her physical fragility often interfered with her work and travel. In 1905, her health prompted a sojourn to Colorado and then Wyoming, where the drier climate was thought to be more beneficial for her condition.

During this time, she didn’t retreat from life but adapted to her circumstances. She worked when she could, continued writing and editing, and spent time reflecting. These years also mark a turning point—a transition from the transience of youth to a period of greater stability and personal resolve.

Around 1907, she returned to South Dakota and took up homesteading near Topbar, a small, wind-swept patch of prairie. For several years, she split her time between the remote shack on her claim and her family home in De Smet. Living alone in a tar-paper shack was not an easy life, but it embodied the pioneer spirit Carrie inherited from her parents. It was also during this time that she began to accept her independence as both a strength and a necessity.

Life in Keystone and Marriage

In 1911, Carrie was assigned to the Black Hills region to oversee newspaper operations. It was there, in Keystone, South Dakota, that her life took a dramatic and permanent turn. The rugged town, known for mining and later for Mount Rushmore, was where she met and married David N. Swanzey in 1912.

David was a widower with two children—Harold and Mary. Unlike her sisters Laura and Grace, Carrie married relatively late in life, at age 42. Yet the marriage seemed one of companionship and mutual respect. David worked as a miner and was also involved in the selection of Mount Rushmore’s location, a legacy that still echoes in South Dakota’s historical records.

Harold, David’s son, became one of the 400 workers who carved the massive granite faces into the Black Hills. Through her marriage, Carrie became part of a different kind of historical narrative—not one penned in books but etched in stone.

Though never a biological mother, Carrie helped raise David’s children and played an active role in their lives. She continued working in journalism to some degree, though her primary focus shifted toward caregiving, both for her husband’s family and later for her sister Mary.

A Lifetime of Care

Of all her roles—printer, journalist, wife, stepmother—the one that perhaps best reveals Carrie’s depth of character is that of caregiver. After their mother died in 1924, Carrie took on the care of her blind sister Mary, a responsibility she maintained until Mary’s death in 1928.

This role, like so many others in Carrie’s life, was performed without fanfare. Yet it required immense patience, empathy, and strength. Carrie ensured that Mary remained comfortable and connected to family life, despite her isolation. This bond between the sisters—quiet, enduring, and grounded in love—stands in stark contrast to the fame and acclaim Laura would receive. Yet it is no less moving or meaningful.

Carrie’s devotion to her family remained steadfast throughout her life. She maintained correspondence with her sisters, nieces, and nephews, and stayed involved in her community in Keystone. Despite battling ill health and enduring significant personal loss, she continued to serve as a stabilizing and nurturing presence.

Legacy and Later Years

Caroline “Carrie” Ingalls Swanzey died on June 2, 1946, in Keystone, South Dakota, at the age of 75. Her life, spent mostly out of the limelight, was one of quiet courage and steady contribution. She had outlived all her siblings except for Grace, and her passing marked the end of a remarkable chapter in the Ingalls family saga.

Today, her memory is kept alive not only through the writings of Laura but also in the town of Keystone, where the local historical museum celebrates her life each year. Her birthday is observed with cake, crafts, and pioneer-themed events—a celebration not just of Carrie Ingalls, but of the values she embodied: resilience, hard work, and grace under pressure.

In many ways, Carrie represents the unsung heroes of the American frontier—those who did not write the stories but lived them. Her life may have lacked the drama of fame or the flourish of fiction, but it was rich in purpose and full of meaning.

Conclusion: The Quiet Legacy

Caroline “Carrie” Ingalls Swanzey may not have left behind volumes of written work or dramatic tales of hardship overcome by triumph. But what she did leave behind is equally valuable: a model of perseverance, quiet dedication, and inner strength. She lived through an era of dramatic social and technological change, witnessed the transformation of the American West, and contributed meaningfully through her work, her relationships, and her spirit.

In remembering Carrie, we are reminded that not all heroes are loud. Some change the world not with a pen or a sword, but with compassion, resolve, and the ability to endure. Her story is a vital thread in the larger fabric of the Little House legacy and the American pioneer experience.