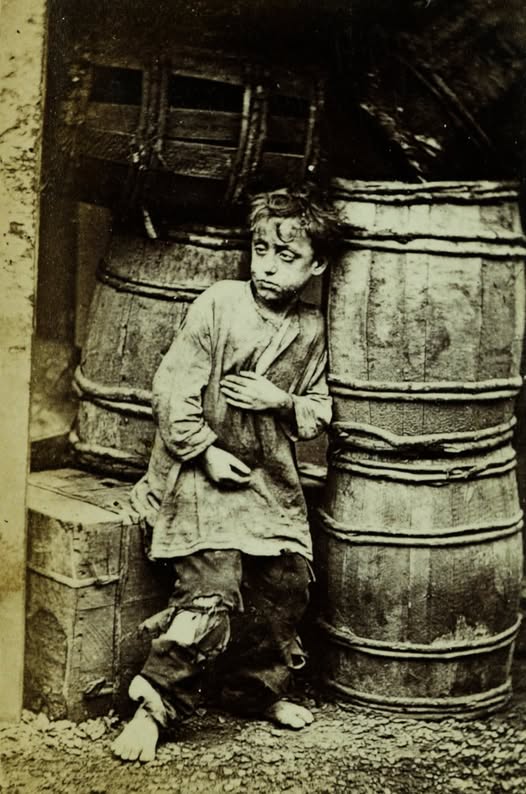

In the shadowed alleys of 1860s Whitechapel, East London, the air was thick with soot and sorrow. It was a place where the poor huddled against crumbling walls, children begged in the streets, and disease spread like wildfire through the overcrowded tenements. In this world of grim survival, hope was a rare and precious thing.

It was here, amid the wretched streets, that a young Irishman named Thomas Barnardo walked, unaware that a single encounter would alter not only his destiny but also the fate of thousands of forgotten children.

Born in Dublin in 1845, Barnardo had initially come to London to train as a medical missionary. His dream was to carry the Gospel and medical aid to China. But London itself proved to be a mission field more desperate and urgent than anything he had imagined. The East End was a place of shocking poverty, hidden in plain sight of the wealthy city center. Here, the Industrial Revolution had produced immense riches for some and unbearable misery for others. And it was here that Thomas Barnardo’s true calling would reveal itself.

One evening, while making his way through the filthy backstreets, Barnardo met a young street urchin—barefoot, ragged, and cold. The boy, no older than ten, had been orphaned by disease and left to fend for himself. He was one of countless children abandoned by a society that had no place for the unwanted. When Barnardo spoke to him, he learned the grim truth: there were no homes, no shelters, and no future for boys like him.

Something deep inside Barnardo stirred—an indignation, a heartbreak, and above all, a sense of responsibility.

That night, he resolved to act.

The First Step: Shelter and Hope

Barnardo’s first act was simple but profound. He took the boy in, providing not just food and a bed, but also warmth, conversation, and care—things the child had been cruelly denied. This small gesture, almost instinctive in its humanity, was the seed from which a mighty tree would grow.

Barnardo realized that if one child could be saved, so could many more.

Fueled by determination and faith, he rented a small house in Stepney, turning it into a shelter for homeless boys. It was modest at first—just a few beds, meager rations, and volunteer teachers—but it was a start. Word quickly spread through the slums: there was a place where no child would be turned away.

This principle became the bedrock of Barnardo’s work. In an era when many orphanages and charities operated with rigid rules—accepting only “deserving” children deemed worthy of aid—Barnardo threw open his doors to all.

“No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission,” a sign at the entrance would eventually declare.

It was a revolutionary idea at a time when the poor were often blamed for their own suffering.

Barnardo rejected judgment in favor of compassion.

Building a Movement

The need was overwhelming. Each night, Barnardo was greeted by dozens of hungry, sick, and desperate children. Some were runaways fleeing abusive homes; others were orphans of disease or industrial accidents. Many had never seen the inside of a schoolroom. Some barely spoke intelligible English, their speech warped by street slang and survival.

Barnardo realized that feeding and housing these children was not enough.

If they were to have any hope of escaping the cycle of poverty, they needed education, skills, and self-respect.

Thus were born the ragged schools — institutions for the poorest children of the East End. In dingy halls lit by flickering lanterns, volunteer teachers taught reading, writing, and arithmetic. But they also taught trades: carpentry, printing, sewing, cooking. Barnardo believed that knowledge was power, and he was determined to give these children the tools to build a better future.

In addition to skills, Barnardo’s schools taught morality, hygiene, and hope. Children who had once known only cruelty and indifference began to blossom under the care of those who believed in them.

It wasn’t easy. Critics accused Barnardo of encouraging idleness and dependency. Some called his homes breeding grounds for crime. Landlords refused to rent to him. The local authorities, overwhelmed and indifferent, offered little support.

But Barnardo pressed on.

Because he had seen the faces of the forgotten, and he could not unsee them.

Tragedy and Resolve

In 1870, a tragedy further strengthened Barnardo’s resolve. A young boy named John Somers, nicknamed “Carrots” for his red hair, was turned away from the shelter because it was full. A few days later, he was found dead—frozen and starved on the streets.

Barnardo was devastated.

He had sworn to help, and he had failed.

It was a moment that seared itself into his soul.

From that day forward, Barnardo vowed that no child would ever again be refused.

If there was no bed, they would sleep on the floor.

If there was no food, they would share what little they had.

If there was no space, they would make space.

The sign went up over the door: “No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission.”

It was more than a slogan; it was a sacred promise.

Expansion and Innovation

Over the next decades, Barnardo’s work expanded rapidly. He established:

- Girls’ Homes, offering refuge to young women at risk of exploitation.

- Convalescent Homes, providing medical care to sick and disabled children.

- Training Farms, where older boys could learn agricultural skills and prepare for emigration to countries like Canada, where labor was in demand.

- Foster Care Programs, placing children with vetted families in the countryside.

- Boarding-Out Schemes, offering a home-like environment instead of institutional life.

Barnardo was not content with traditional charity models. He innovated constantly, adapting to new challenges and always putting the child’s welfare first. He documented his work with photographs — haunting images of the “before” and inspiring images of the “after” — to raise awareness and funds.

He used storytelling as a tool for change, sharing the real, raw experiences of the children he helped.

He understood that empathy could move mountains.

Criticism and Controversy

As Barnardo’s influence grew, so too did criticism. Some accused him of kidnapping children, claiming he exaggerated their conditions to justify intervention. Legal battles ensued, with Barnardo sometimes at the center of fierce public debates.

Yet even his detractors often admitted that his methods, however unorthodox, were driven by genuine concern.

In a time when the poor were largely invisible to the powerful, Barnardo forced the nation to look, to see, and to care.

He also faced personal trials: fragile health, endless fundraising battles, and the crushing weight of responsibility for thousands of lives.

Yet he persevered.

Barnardo often said he was guided by a simple principle: “God and the children first.”

The Final Years and Legacy

By the time of his death in 1905, Barnardo’s achievements were staggering.

- Over 60,000 children had been rescued and given new lives.

- Hundreds of homes, schools, and training centers had been established.

- Countless more had been reached through education and advocacy.

But Thomas Barnardo’s true legacy was not in the numbers.

It was in the lives he touched — the boys who became carpenters, farmers, teachers, husbands, fathers; the girls who grew into strong, independent women; the generations who rose from the gutters of Whitechapel to build lives of dignity and purpose.

Today, Barnardo’s, the charity that bears his name, continues his mission.

It supports vulnerable children across the UK, tackling issues from poverty and homelessness to abuse and mental health.

It adapts to modern needs, but it remains true to its founder’s belief:

No child should be abandoned. Every child deserves a chance.

A Light That Never Fades

In the alleys of Victorian Whitechapel, hope must have seemed like a foolish dream.

But because of one man — a young Irish doctor who listened to the pain of a single child — a new light was kindled.

It was not a blaze that would burn itself out in a moment of passion, but a steady flame, passed from hand to hand, generation to generation.

Thomas Barnardo did not change the world overnight.

He changed it one child at a time.

And in doing so, he taught us a lesson that still echoes across the decades:

The greatest revolutions are born not from grand gestures, but from small acts of compassion, multiplied by courage and faith.

The boy in the alley was not just a victim of poverty.

He was a messenger.

And Barnardo was wise enough to listen.

In every child rescued, every life transformed, his legacy lives on — a quiet, persistent miracle.

A reminder that even in the darkest of places, there is always room for hope.