When you think of the giants of prehistory, dinosaurs with teeth like steak knives might spring to mind, or enormous marine reptiles slicing through ancient seas. But long after the non-avian dinosaurs had vanished, South America was home to some of the most fearsome avian predators ever to stride the Earth — the phorusrhacids, or “terror birds.” Among these remarkable apex predators was Mesembriornis, a swift, deadly, and highly specialized hunter that terrorized its prey in the open grasslands of prehistoric Argentina.

Mesembriornis belonged to a branch of flightless birds that evolved in isolation on the South American continent after it split off from other landmasses. For millions of years, mammals elsewhere dominated predator roles, but in South America, birds took on that mantle, evolving into powerful ground-dwelling hunters. Unlike modern ostriches or emus, which are largely peaceful herbivores, Mesembriornis was a meat-eater, equipped with a hooked beak, powerful legs, and a head and neck designed to seize and kill prey with brutal efficiency.

This incredible bird lived during the Late Miocene to Pliocene epochs, roughly 6 to 3 million years ago, a time when South America was teeming with unique, often bizarre animals found nowhere else on the planet. Fossils of Mesembriornis have been uncovered primarily in Argentina, providing paleontologists with precious clues about its build, its lifestyle, and its role in prehistoric ecosystems.

Meet the Terror Birds

To truly understand Mesembriornis, we have to place it in its wider family: the phorusrhacids. These were a group of large, carnivorous flightless birds whose fossils have been found across South America. Phorusrhacids evolved in the Paleocene or Eocene and lasted until perhaps as recently as the Pleistocene. Some members grew absolutely gigantic, standing three meters tall and weighing over 200 kilograms.

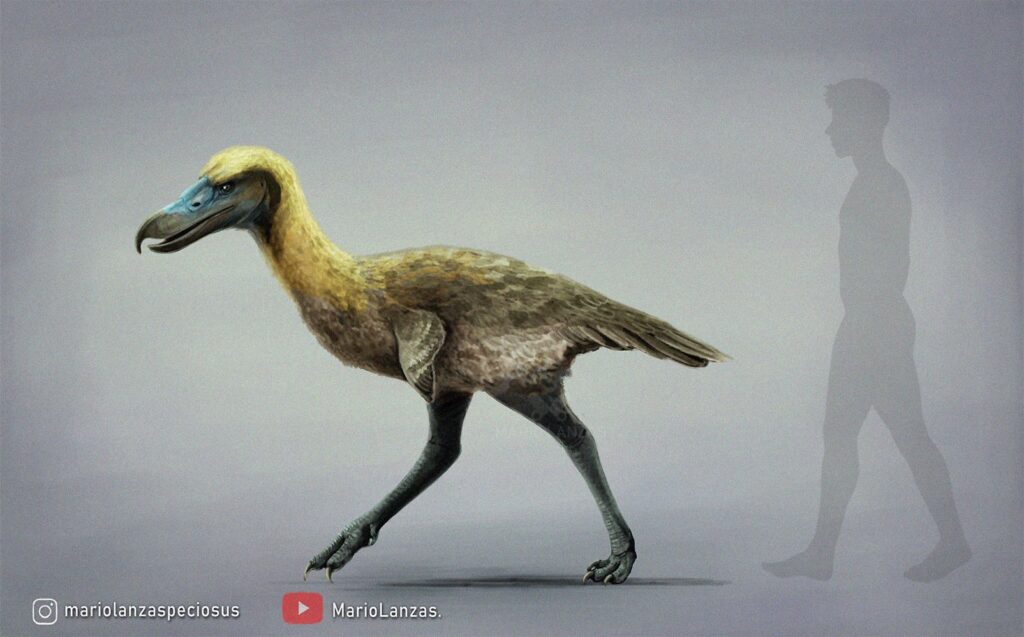

But Mesembriornis was a more medium-sized terror bird — estimated at about 1.5 to 2 meters tall (5–6 feet), with long, powerful legs made for running down prey. Its family, the Mesembriornithinae, was especially adapted for speed. Unlike the heavier and bulkier phorusrhacids like Kelenken or Titanis, Mesembriornis was built for chasing prey across open grasslands, much like a cheetah among the birds.

The name Mesembriornis itself means “Southern bird,” reflecting its southern South American fossil range. Within its environment, it was a top predator, hunting small to medium-sized mammals, reptiles, and possibly even other birds. Its hunting style would have been a sight to behold: a sprinting, clawed, long-legged killer with a beak built to deliver a fatal strike.

Discovery and Scientific Research

The first remains of Mesembriornis were described in the late 19th century, during a period when South American paleontology was truly taking off. Argentine scientists and traveling naturalists were stunned by the diversity of fossil animals in the Pampas and Patagonian regions. Giant ground sloths, saber-toothed marsupials, ancient armadillos called glyptodonts, and of course, the terror birds all emerged from the sediments.

Fossil collectors soon realized that they were dealing with birds unlike any known today — birds with the body of an oversized raptor but flightless, and with legs built for running, not perching. The powerful hooked beak, a trait shared among terror birds, was a giveaway: these were not gentle giants.

Over time, paleontologists pieced together the family tree of these giant birds. They recognized that Mesembriornis belonged to a subgroup distinct from the taller, more robust phorusrhacids. Its fossils showed longer, more gracile legs, indicating a different strategy — more about speed and pursuit than brute force alone.

Life and Behavior

What did a day in the life of Mesembriornis look like?

Imagine the ancient Argentine plains, filled with grazing mammals related to notoungulates, grazing toxodonts, and smaller rodent-like animals. Perhaps a herd of litopterns — hoofed mammals vaguely reminiscent of antelope — passes through the grass. Suddenly, from cover, Mesembriornis bursts into motion, legs pumping, beak open, eyes fixed on a fleeing prey. Its long legs close the distance rapidly, and with a powerful strike of its beak, it seizes its quarry, delivering a killing blow with that deadly curved tip.

Unlike some of its larger relatives, Mesembriornis might have depended on endurance running and rapid acceleration to catch prey, rather than ambushing from close range. Its skeleton supports this: a lightweight but strong frame, large muscle attachment areas on its leg bones, and a flexible neck designed to whip the head forward in a powerful strike.