In a world that often values academic achievements as the key to success, stories like that of Konosuke Matsushita stand out as a testament to human resilience, ingenuity, and the power of vision. Despite struggling with reading and writing during his childhood, Matsushita went on to found one of the world’s largest and most respected technology companies — Panasonic. His journey from poverty and hardship to global entrepreneurship challenges conventional ideas about education, success, and innovation.

Matsushita’s story is not just about building a business empire. It is a story about grit, determination, and an unwavering belief in a dream. Born into a poor family, deprived of formal schooling, he learned through his hands and mind, exploring the mysteries of electricity and mechanics. He faced countless setbacks, including rejection by those in power and the hardships of economic instability, wars, and natural disasters. Yet, he never lost sight of his vision: to create technology that improves everyday life for people everywhere.

This essay will explore the remarkable life of Konosuke Matsushita, tracing his early years, his hands-on learning, his innovative spark, the birth of Matsushita Electric, and the company’s evolution into Panasonic. Along the way, we’ll discover powerful lessons about creativity born from poverty, the strength to persevere through failure, and the vital role of visionary leadership. Matsushita’s life is an inspiring reminder that no matter the obstacles, with hope and determination, anything is possible.

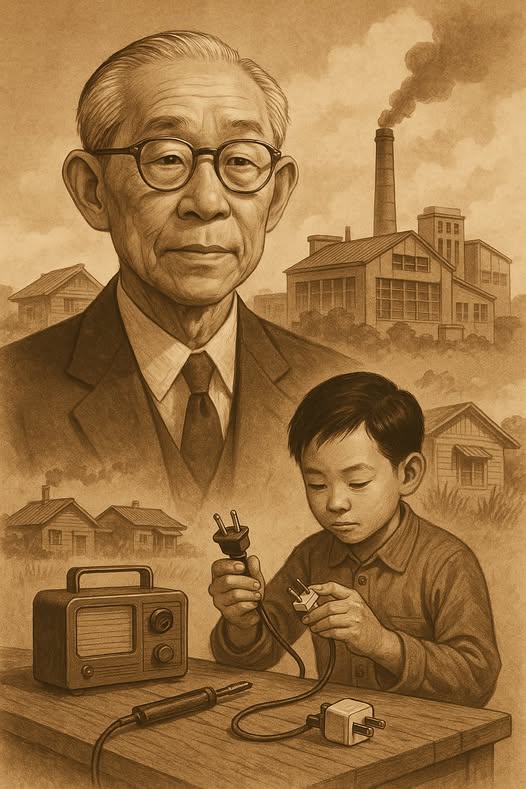

Konosuke Matsushita was born in 1894 in a small town in Japan. From the very beginning, life was a storm of challenges. His family was poor, living hand to mouth, and education was a luxury they simply could not afford. Unlike many children who had the chance to attend school regularly and learn to read and write fluently, Matsushita’s formal education was cut short at an early age. By the time he was nine years old, he had already dropped out of school to work.

The decision to leave school was not voluntary in the traditional sense; it was a harsh necessity driven by the economic conditions of his family. His parents needed all hands to contribute to the household income, and schooling, with its expenses and time commitment, was a distant dream. While most children were learning from books, Matsushita was learning from the rough, tangible world around him. His classroom became the bustling bicycle repair shop where he worked as an apprentice.

Working with his hands every day taught Matsushita things no book could. The mechanical parts of bicycles — chains, brakes, wheels — were puzzles waiting to be solved. His mind became a laboratory of curiosity, endlessly probing how things worked, how parts fit together, and how motion could be harnessed and controlled. Despite his inability to read well, he developed a profound practical intelligence, a skill set often underestimated but critical for the innovations he would later pioneer.

At some point during these early years, Matsushita encountered electricity — a force that fascinated him deeply. Electricity represented the future, a new frontier where he saw opportunity. While others might have been daunted by the technical complexity or his own literacy challenges, Matsushita’s curiosity burned brighter. He realized that if he could understand and harness electricity, he could help build the future.

This period of childhood and apprenticeship was not easy. There was hardship, physical exhaustion, and the weight of poverty pressing down. But there was also a growing spark of hope. Matsushita’s life was shaped not by formal schooling but by the lessons of resilience, curiosity, and the tangible experience of working with his hands. These foundations would later become the bedrock of his success.

Apprenticeship and Learning by Doing

The bicycle repair shop where young Konosuke worked was a world unlike the classrooms of traditional education. It was filled with the sounds of metal scraping, the smell of oil and grease, and the steady rhythm of manual labor. For many, this environment might have seemed limiting or discouraging. For Matsushita, however, it was a treasure trove of lessons. Here, he learned that knowledge was not confined to books or classrooms; it was everywhere, waiting to be discovered by those willing to observe, experiment, and persist.

Despite his difficulties with reading and writing, Matsushita’s mind was sharp and his hands steady. He became adept at repairing, assembling, and understanding complex mechanical systems. Each broken bicycle part was a puzzle to be solved, a challenge to be overcome. His apprenticeship wasn’t just about learning how to fix bikes; it was about learning how to think like a problem solver — to approach obstacles methodically and creatively.

This practical education was crucial. While many around him focused on academic subjects, Matsushita’s lessons came from trial and error. He learned how to disassemble complicated mechanisms, identify faulty components, and improvise repairs with limited resources. This kind of learning fostered a deep understanding of physical systems and mechanics, essential for his later inventions.

Electricity, in particular, captivated him. Unlike the visible mechanics of bicycles, electricity was invisible and mysterious, yet profoundly powerful. Matsushita began to study basic electrical principles on his own, reading what little he could, and experimenting with whatever tools he could scavenge. His curiosity led him to tinker with electric wires, plugs, and circuits, fascinated by how energy could be controlled and used to power machines and improve everyday life.

Matsushita’s struggles with literacy did not stop him from seeking knowledge. Instead, they pushed him to develop alternative ways of learning — through observation, hands-on practice, and listening carefully to those with technical expertise. This adaptive learning approach helped him build a unique set of skills that were grounded in real-world applications rather than theory.

His apprenticeship also taught him the value of perseverance. Mistakes were inevitable, but each failure was a stepping stone toward understanding. Where many might have given up after repeated setbacks, Matsushita saw each failure as a lesson. This mindset became a defining trait of his character and future leadership.

At this stage, the foundations of his innovative spirit were being laid. By blending curiosity, practical skill, and relentless persistence, Matsushita was preparing himself for the challenges ahead. He understood that true mastery came not from memorizing facts, but from immersing oneself in the craft and never losing the hunger to learn.

The Factory Years — Spark of Innovation

After his apprenticeship, Matsushita found work as a factory laborer. This new chapter was both a step forward and a test of his resolve. Factories in early 20th century Japan were demanding places — noisy, harsh, and filled with endless routines. But for Matsushita, the factory floor was also a place of insight and opportunity.

It was here that he began to conceive the idea of improving electrical devices, particularly the electrical plug. At the time, electrical plugs were unsafe and inefficient. Many households and factories used plugs and sockets that posed risks of electric shock and fires. Matsushita saw a clear problem that needed solving.

Drawing from his hands-on experience and curiosity about electricity, he designed a safer, more reliable electrical plug. This innovation wasn’t just a small technical adjustment — it had the potential to change the way electricity was used in homes and businesses, making it accessible and safe for the average person.

However, this bright idea met with cold reception from his bosses. The factory management, steeped in tradition and cautious about change, rejected his invention outright. They did not believe in his idea and saw no value in disrupting established manufacturing processes. Matsushita’s suggestion was dismissed as impractical and unnecessary.

Facing this rejection was a pivotal moment. Many would have accepted the status quo or given up their dreams. But Matsushita chose a different path — he quit the job. This decision was risky, especially for someone with limited formal education and no financial cushion. Yet, it was also a powerful declaration of independence and belief in his vision.

Quitting the factory was not just leaving a job; it was a leap into the unknown. Matsushita’s confidence in his invention and his desire to bring it to life outweighed the security of a steady paycheck. This moment defined his entrepreneurial spirit — willing to take risks, defy conventions, and pursue a dream despite the odds.