When we think of cities, we often picture concrete jungles, glass towers, and steel bridges. We imagine modernity as a triumph over the natural world—a domain carved by stone and cement. Yet long before these modern materials came to dominate urban landscapes, humankind built its dreams upon humbler foundations. And of all the materials, wood—renewable, workable, and rich with possibility—was perhaps the most essential.

Among the most stunning feats of architecture and human resilience is Venice, a city literally built atop wooden pilings driven into a marshy lagoon. The idea that one of the world’s most iconic and beautiful cities floats on timber is almost too fantastical to believe. Yet it is not alone. Around the world, cities, settlements, and entire cultures have relied on wood not just for building, but for surviving the harsh conditions of geography, climate, and time.

This essay is a deep exploration into the city built on wood—a phrase that serves both as a literal and metaphorical window into the creativity, adaptability, and limitations of human civilization.

Venice, Italy is often dubbed La Serenissima, the Most Serene. But beneath its calm canals lies a chaotic history of survival and ingenuity. Founded in the 5th and 6th centuries by refugees fleeing barbarian invasions, Venice was born not on solid land but in the silted shallows of the Venetian Lagoon.

Why would anyone build a city here? The answer was both strategic and symbolic. The lagoon offered safety—its murky, shifting channels were difficult for invaders to navigate. It was a refuge, a last stand of Roman civilization as empires crumbled.

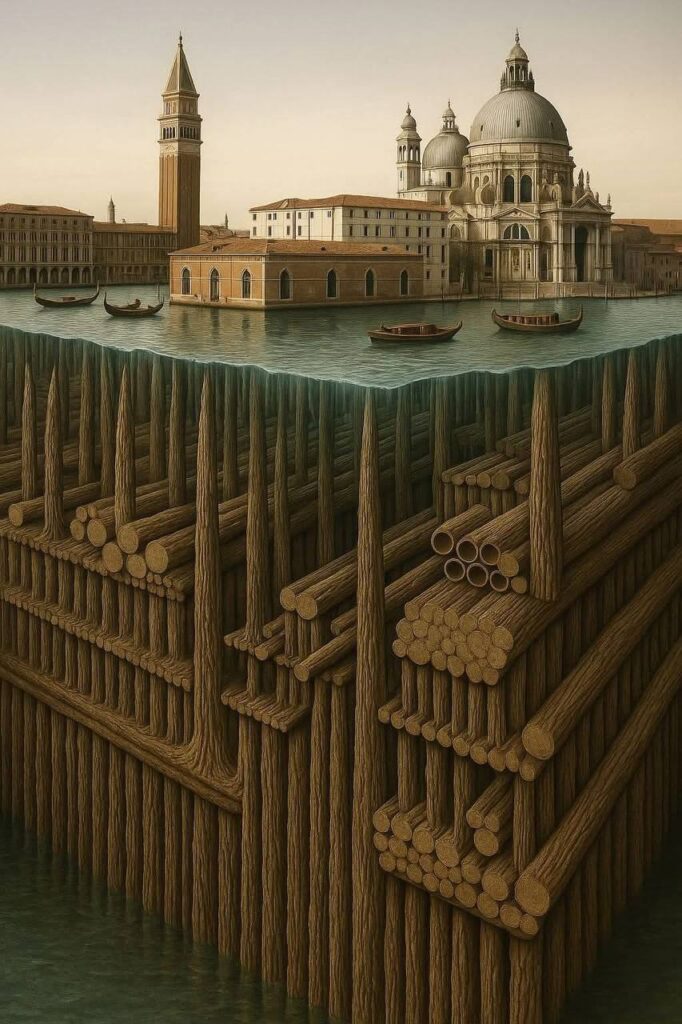

But how do you build a city on waterlogged land? The Venetians used a remarkable solution: millions of wooden piles, primarily from oak, alder, and larch, were driven into the mud. On top of these timber foundations, platforms of Istrian stone—a dense, water-resistant limestone—were laid. Buildings rose atop these wooden forests, and Venice began to take shape.

Here is the astounding part: the wood didn’t rot. Submerged in the oxygen-poor, mineral-rich waters of the lagoon, the timber petrified over time. Hardening like stone, these submerged wooden foundations still support Venice today, over a thousand years later.

Venice is, quite literally, a city built on wood—and held up by it for centuries.

Venice may be the most poetic example, but it is not unique in its dependence on wood. From the Viking longhouses of Scandinavia to the medieval towns of Germany and Eastern Europe, wood was the primary building material for centuries.

Cities like Novgorod and Moscow were once dominated by wooden architecture. So were towns across Japan, Korea, and China, where temple complexes and entire castles were built of intricately interlocked timbers. In many of these places, wood was not only material—it was metaphor. In Shinto tradition, for instance, wood is sacred, and the rebuilding of the Ise Grand Shrine every 20 years honors the impermanence of life.

In the Americas, Native peoples such as the Haida and Tlingit of the Pacific Northwest built longhouses and totem-lined villages entirely of red cedar. In the Amazon, wooden stilt homes known as palafitas rose above flood-prone banks. In Southeast Asia, wooden floating villages and bamboo homes still hug the edges of lakes and rivers.

Wood was everywhere—not just because it was available, but because it worked. It was strong, flexible, renewable, and relatively easy to transport. The entire pre-industrial world, to a significant degree, was built on wood.

But wood has a dark twin: fire. The very thing that made timber so accessible—its flammability—also made it vulnerable.

History is scarred by great fires that consumed wooden cities. The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed over 13,000 buildings, reshaping the city forever. Fires swept through Edo (Tokyo), Chicago, and countless medieval towns, often leaving nothing but ash.

In response, cities rebuilt—sometimes again with wood, sometimes shifting toward stone or brick. But the cycle of wood, fire, and rebirth was an essential rhythm of urban life.

Paradoxically, this cycle also preserved cultural memory. Each rebuilding brought innovations, stronger methods, and sometimes, monumental shifts in urban planning. Wood demanded resilience—not just from structures, but from the people who lived within them.

To think of wood solely as a construction material is to miss its deeper meaning. Across cultures, wood has been imbued with symbolism, spirituality, and sensuality.

In Japanese architecture, the patina of weathered wood, the softness of grain, and the scent of cedar are all part of an aesthetic known as wabi-sabi—the beauty of imperfection and impermanence.

In Northern Europe, stave churches with their intricate carvings became cathedrals in the forest. In China, Confucian scholars revered the wood-block prints and calligraphy carved onto elm and boxwood. In the American frontier, log cabins were not just shelters—they were statements of independence.

Even today, architects prize wood for its warmth and emotional resonance. A wooden house feels different from a concrete apartment. It creaks, it breathes, it lives with you. This intimacy has kept wood relevant, even in the age of steel and glass.

Let us return to Venice—the impossible city that still rests on timber. How does it survive?

Modern engineers have studied the wooden foundations and discovered an astonishing fact: the wood remains stable precisely because it is submerged. Exposed to air, it would rot. But under water, in anaerobic mud, it endures.

Even today, some of Venice’s buildings lean slightly—some dangerously. Rising sea levels and increased flooding (the infamous acqua alta) threaten its delicate balance. But so far, the city holds. Restorers and engineers use sonar, x-rays, and underwater cameras to monitor the wood. In some cases, they reinforce it—not with replacement, but with care. The goal is not to erase the past, but to preserve it.

Venice is more than a tourist marvel. It is a living laboratory of wooden urban resilience.

In the 21st century, wood is making a comeback.

As climate change forces architects to rethink carbon-heavy materials like concrete and steel, mass timber has emerged as a sustainable alternative. Cross-laminated timber (CLT), glue-laminated beams, and other engineered woods offer strength, fire resistance, and renewability.

Modern cities like Oslo, Tokyo, and Vancouver are experimenting with wooden skyscrapers. Schools, libraries, and even train stations are being built from timber again—not because it’s old, but because it’s smart.

This reemergence is not nostalgia. It is innovation rooted in ancient wisdom. Venice teaches us that wood, when used wisely, can support empires. Now, it may help save the planet.

To say a city is “built on wood” is to suggest more than construction. It is to say that a city was born of improvisation, necessity, and faith in the everyday. Wood is not impervious like stone. It demands maintenance, attention, and presence. Living in a wooden city means accepting that time will leave its mark.

That humility may be one reason why wooden cities feel more human. They bend. They warp. They whisper in the wind. They teach patience and respect for nature.

In a world obsessed with permanence and perfection, wood reminds us that beauty lives in transience.

The city built on wood is not just a place—it’s a philosophy. It says, “We adapt. We honor the earth. We build not to dominate, but to live in harmony.” From the marshes of Venice to the forests of Scandinavia to the mountain temples of Asia, wood has borne our weight and our stories.

Today, as we face ecological crises and a search for sustainable ways of living, the lessons of wooden cities are more urgent than ever. They teach us resilience, respect, and reverence for the materials we use. They show us that strength can come from flexibility—and that survival sometimes floats on the softest foundation.

So let us not forget: the city built on wood is not a relic. It is a guide.

It is, in every sense, still standing.